By Crystal Zimmerman

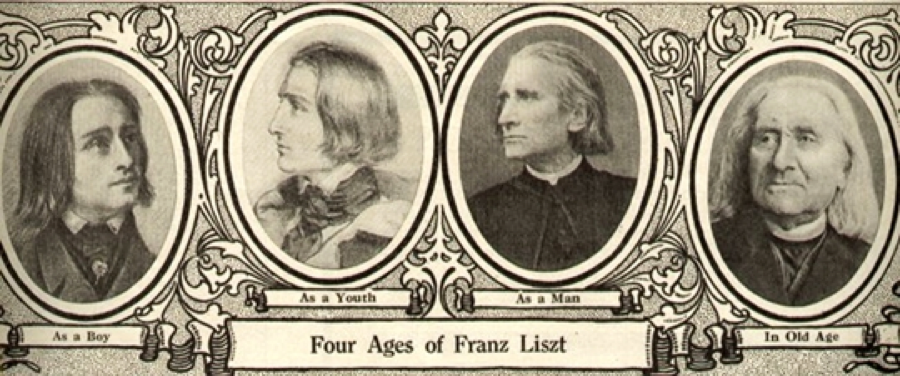

The Four ages of Franz Liszt, as published in The Etude magazine, 1913.

The Four ages of Franz Liszt, as published in The Etude magazine, 1913.

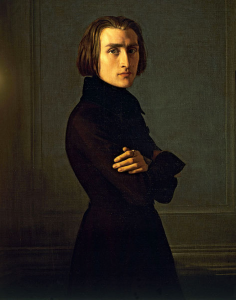

Young Liszt

On Tuesday, October 22, 1811, an extraordinary child was born. Franz Liszt was born to Adam and Anna Liszt in Raiding, a German-speaking region of Hungary.

As a child Liszt was constantly exposed to music. His father was employed as an accountant of sheep at the Esterházy estate, but was also an amateur cellist, pianist, violinist, and had a beautiful singing voice. Music-making occurred often in the house, with regular chamber music evenings that brought visitors from the neighborhood. Adam Liszt saw in his son a natural talent almost immediately and began teaching young “Franzi” piano.

Birthplace of Franz Liszt in Raiding

Young Liszt rapidly progressed in his studies. In 1822, he had moved to Vienna where he could study with the famed pianist and pedagogue Carl Czerny. For the continued education of theory and composition, Liszt studied with Antonio Salieri. Liszt’s natural talent was obvious from the start. The young boy’s playing was magical; he could improvise any given tune and sightread most scores. These instructors, impressed by Liszt’s abilities, taught free of charge.

By the time Liszt was 9 years old, he was touring as a concert pianist. During this time, Liszt was limited to the companionship of his father. However, in 1827, Adam and Franz decided to take a break from touring and visited Boulogne. During this trip, Adam Liszt fell ill with typhoid and died at the age of 50. Franz was left alone with major responsibilities at the young age of fifteen. Up until this point, Adam had organized everything for Franz – from travel accommodations to concert appearances. Without his father, young Liszt was unsure how to proceed, thus he traveled back to Paris to join his mother. In Paris, Liszt began teaching and formed his first love affair with Caroline de Saint-Cricq. Unfortunately things did not work out, causing Liszt much heartache, so much so that he suffered a nervous breakdown. When life was collapsing around him, he turned to faith. Rather than write music, he spent hours at the Church of St-Vincent-de-Paul. Again he begged to enter the seminary and devote his life to God, and again he was discouraged by others.[1]

Franz Liszt Lithograph by Charles Etienne Pierre Motte ca. 1827

http://www.library.yale.edu/musiclib/exhibits/liszt/liszt_lithograph_young.html

Life in Paris:

Liszt remained with his mother in Paris for the next several years. In Paris he lived a quiet life while continuing to endure feelings of depression and lethargy. It wasn’t until after the “Three Glorious Days” of 1830, when the streets of Paris were barricaded and bloody combat ensued, that Liszt was awakened from his state of despondency. The sound of gunfire and fighting inspired him to return to composition. Anna Liszt reflected afterwards saying, “The guns cured him.”[2] Liszt was soon mingling with aristocracy, artists, musicians and literary figures in the famous Parisian salons.

Eugène Delacroix – La liberté guidant le people

During his stay in Paris, Liszt met many influential people. He was surrounded by some of the most accomplished pianists in Europe, including Thalberg, Pixis, Kalkbrenner, Hiller, Cramer and the famous composers Berlioz, Chopin, and Mendelssohn. On April 20, 1832, Liszt attended a concert by the renowned violinist virtuoso, Niccolò Paganini. Liszt was so impressed by Paganini’s extreme mastery of the violin, that he swore then, that at the piano, he would one day be able to have the same control, skill, and technical prowess. It was also at this time Liszt began to manifest his own sense of validity as an artist. Talent was to be used to serve humanity, not oneself – “génie oblige!”

Liszt and the Countess:

In 1833, Liszt met Countess Marie d’Agoult, who would change the course of his life. The countess was married to a French cavalry officer named Charles Louis Constant d’Agoult and had two children. By March 1835, the Countess was pregnant with their first child. Staying in Paris was no longer an option, as the scandal was overwhelming. The new lovers planned a secret honeymoon to Switzerland. In 1835, the Countess joined Liszt in Geneva, leaving behind her husband and child. While in Switzerland, Blandine was born on December 18. During that time, Liszt taught at the newly established Geneva Conservatory of Music and wrote articles for a publication, the Paris Revue et gazette musicale. Liszt was inspired not only by his relationship with Marie and the birth of their child, but also by the beautiful countryside. These years were very productive for the composer, and resulted in several masterpieces – the Études d’exécution transcendante and the Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, as well as the Années de pèlerinage.

Portrait of Franz Liszt, 1839

Henri Lehmann

Portrait of Marie d’Agoult, 1843

Henri Lehmann

Between 1835 and 1839, Liszt and the Countess traveled extensively, while keeping their home primarily in Switzerland and Italy. In 1837, Liszt participated in the famous “ivory duel” with Sigismond Thalberg at the home of Princess Cristina Belgiojoso on March 31. The princess diplomatically declared: “Thalberg is the first pianist in the world – Liszt is unique.” During this year the couple explored Lake Como and the surrounding countryside. In Bellagio their second child Cosima arrived on December 24, 1838.

In March of 1838, Liszt heard of a terrific tragedy that inspired him to return to the concert platform; in Hungary, his homeland, the frozen Danube melted and the resulting flood was devastating. During this national crisis, Liszt gave concerts in Vienna and donated the largest single gift to Hungary from a private individual. These concerts not only aided the homeland for which he had much affection, but brought the virtuoso pianist back into the spotlight.

Liszt and Marie d’Agoult eventually traveled to Rome. Here, the illustrious city and the great history of Italian masters of art and literature inspired Liszt. Their third child, Daniel, was born on May 9, 1839. Through the travels of Italy, and especially the Holy Roman city, Liszt began the Années de pèlerinage, Book II, which reflects Italian art, painting, sculpture, and poetry.

Franz Liszt Fantasising at the Piano (1840) by Josef Danhauser – depicting Liszt playing in a Parisian salon on a grand piano made by Conrad Graf, who commissioned the painting; on the piano is a bust of Ludwig van Beethoven by Anton Dietrich; the imagined gathering shows seated Alexandre Dumas, George Sand, Franz Liszt, Marie d’Agoult; standing Hector Berlioz or Victor Hugo, Niccolò Paganini, Gioachino Rossini; and a portrait of Byron on the wall.

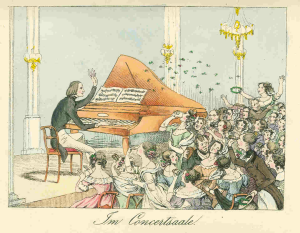

Liszt spent the next eight years as a touring concert pianist, a time often labeled as his “years of transcendental execution.” Pianists today are indebted to him for the many innovations of the standard concert model. Liszt was the first pianist to play entirely by memory, the first to turn the piano with the lid opened towards the audience, the first to use the term “recital,” as if delivering a recitation that has been prepared and memorized, and the first to play an extensive piano repertoire from Bach onwards. His concerts spanned the years 1839-1847. He traveled all across Europe: Germany, France, Spain, Holland, Switzerland, Portugal, Britain, Austria, Romania, Russia, Ireland, Romania, and Turkey. His concerts in Hungary were especially moving, as he had not seen his homeland in 16 years, and now was one of the most famous Hungarians alive. To show their admiration and respect for this national hero, Liszt was given the sword of honor on January 4, 1840. In his homeland, Liszt started the series of Hungarian Rhapsodies as he was once again captivated by the improvisational inventiveness of the Gypsy musicians, whose music would inspire him throughout his life.

Liszt became was a huge success. Not only was he a spectacular pianist, capable of amazing technical feats, but he was also magnificent to watch, a spirit overcome by the transcendent magic of music, thus epitomizing the ideal of romantic artist and hero. The German literary writer and romantic poet Heinrich Heine described the sensational public response as Lisztomania. Liszt’s magnetic personality and electrifying piano pyrotechnics incited hysteria. Much of his reputation as a virtuoso was developed during these years; yet much of his personal reputation was based on exaggerated accounts, and eventually became myth. In recognition of his abilities, many honors and awards were bestowed upon him, including a pair of dancing bears from Tsar Nicholas I. However, it must also be remembered that though Liszt was earning enormous amounts, most of the money was given to charity and humanitarian causes. His generosity eventually put him into pecuniary straits.

Liszt in the concert hall, 1842,

Theodor Hosemann

Life with his mistress Marie d’Agoult and his three children was still thriving, if only barely. Between 1841 and 1843, the small family saw each other only on holidays in their small retreat at Nonnenwerth. By 1844, the affair was officially over, as Marie became overwhelmingly incensed by his purported affair with the dancer Lola Montez. That Liszt vehemently denied the affair was of no consequence to the already fragile nerves of the Countess. Marie was so angry that, under the pseudonym “Daniel Stern” she published the novel Nelida, in which she portrays a character greatly resembling Liszt in a negative manner.

Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein

In 1846-1847 Liszt began a concert tour of Transylvania, Russia, and Turkey. In September of 1847, at the youthful age of 35, he gave his last public concert in Elisavetgrad, a city in central Ukraine. Russia would forever change Liszt. In the audience of his concert in Kiev was the young Polish heiress, Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein. The young Princess was estranged from her husband Prince Nicholas von Sayn-Wittgenstein, to whom she was forcibly married when she was an adolescent girl. As soon as the couple met, they fell in love, and henceforth the Princess began a painstaking 13-year journey to procure an annulment. The battle was very difficult, as the Princess was massively wealthy, and though the Wittgensteins did not want her, they did want her wealth and assets. Princess Marie, the daughter born of this union, presented an additional complication; an annulment would make the child illegitimate.

Portrait of Carolyne_von Sayn-Wittgenstein, daguerreotype

1847

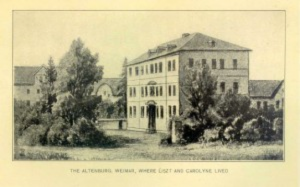

Weimar:

In the year 1848, Liszt settled in Weimar as Kapellmeister-in-Extraordinar, a position offered to him several years earlier by the Grand Duke of Weimar. The city held many promising opportunities; it had an opera house and orchestra where he was invited to conduct, and above all, the city offered him time, thus allowing him the luxury to compose. With his newfound freedom from the concert platform, he was now able to embark on many other musical pursuits. Liszt lived with Princess Carolyne in his home, the Altenburg, a residence that would soon become synonymous with fine music and musicians. Liszt taught some of the next generation’s most remarkable pianists including Hans von Bülow, Peter Cornelius, Karl Klindworth, Carl Tausig, and William Mason while entertaining extraordinary musicians, painters, and politicians as guests.

In Weimar Liszt became engaged in the “War of the Romantics,” a battle between the Leipzig conservatives including Brahms, Schumann and Mendelssohn, and the progressives in Weimar including Liszt, Wagner, and Berlioz. The arguments centered around program versus absolute music, and the future of sonata form and harmony. In simple terms, this was a battle between music of the future and music of the past.

Liszt ardently endorsed the music of Wagner and Berlioz, arranging festivals specifically featuring their innovative compositions. Also in Weimar, Liszt offered a radical solution with regard to structure by introducing into his compositions cyclic conceptions and thematic transformation. He encouraged music to move beyond sound, and allowed it to transform into an art form capable of depicting an image. All three concepts can be seen in the three books of Années de pèlerinage.

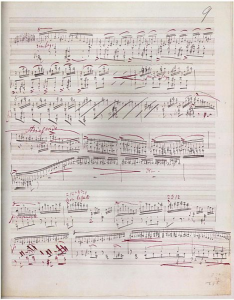

While in Weimar, Liszt was not only working to promote the music of the future through the New German School, but was also busy with many other activities. Most notable was his creation of piano compositions, including the Piano Sonata in b minor. At the same time he was working on compositions for larger orchestral forces, culminating in the now famous Faust-Symphonie. He would regularly conduct, with never-before-seen techniques, dramatic motions, and unorthodox and innovative body motions. He was also a writer, scholar, and editor. In 1853 Liszt coined the phrase “Symphonic Poem” to designate his one-movement symphonic works, in which his compositional techniques proved to be revolutionary for future generations of composers.

Page 11 of manuscript of Sonata in B minor by Franz Liszt, 1853

Throughout his thirteen years at the Altenburg, Princess Carolyne was a constant source of comfort and support, both spiritually and intellectually. She reignited his passion for his faith, encouraging daily prayers and blessings upon their relationship. The following quotation taken from his will, written in Weimar on September 14, 1860, most eloquently declares his sentiments.

I cannot write her name without an ineffable thrill. All my joys are from her, and all my sufferings go to her to be appeased. Not only has she become associated and completely identified with my existence, my work, my worries, my career, helping me with her advice, sustaining me with her encouragement, reviving me with her enthusiasm and with her unimaginable prodigality of attentions, anticipations, wise and gentle words, ingenious and persistent efforts; more than that she has often renounced herself, abdicating whatever there is of a legitimate imperative in her nature, the better to bear my own burden, which she had made her wealth and her only luxury.[3]

Unfortunately, the union with Princess Carolyne was not without trouble. She traveled to Rome in 1860, desperate for an annulment, attempting to convince the Roman Catholic authorities that she was forced into marriage. In January of 1861, an annulment was finally granted. Upon hearing this news, Liszt left Weimar to be with the Princess in Rome. The couple had planned to marry on Liszt’s fiftieth birthday in Rome; however, this union would never take place. The struggles with the Wittgensteins (her husband’s family) and the Iwanowskys (her family) were never-ending. The possible negative repercussions from marrying Liszt included being labeled a bigamist and rendering her daughter illegitimate. Thus, the Princess also experienced hostility from her own daughter. All of this malevolence, directed at her from a variety of sources, was primarily due to the immense inheritance that was at stake. With so much conflict, and the repeated failed attempts at gaining an annulment, the couple decided to refrain from a formal marriage. After Carolyne’s husband died in 1864, and there were no impediments for a wedding, the couple still chose not to get married.[4]

The Final Years:

The final years of Liszt’s life were full of tragic events; events that caused the master much pain and sorrow and ultimately affected his musical style. An evolution occurred in which the virtuoso pianist, who had often performed with grandiloquent displays, transformed into a spiritual individual. His music and his playing became increasingly introspective, somber, and contemplative. Liszt’s later works can be understood more thoroughly only after obtaining a full comprehension of his life at this time, as many of the compositions are direct reflections of his personal experiences.

During this time, Liszt experienced several difficult personal tragedies. Liszt’s son Daniel died in 1859, at the young age of 20, from tuberculosis. A short three years later, in 1862, his daughter Blandine died due to complications after giving birth. The death of his children was undoubtedly painful, as he would continuously grieve their loss. In addition, his mother, Anna Liszt, died on February 6, 1866 due to complications caused by pneumonia. Liszt also experienced embarrassment and anguish over the personal relationships of his only remaining child, Cosima. Though she was married to Liszt’s beloved student, the virtuoso pianist and orchestral conductor Hans von Bülow, she began an illicit affair with Liszt’s companion and respected colleague, the famed German composer Richard Wagner.

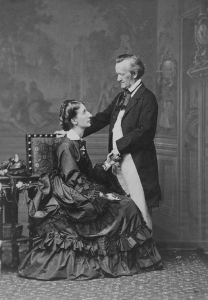

Richard and Cosima Wagner, photographed in 1872

Liszt had always been loyal to the Catholic Church, and during these times of distress he sought solace in the rituals of his faith. In June of 1863, he withdrew to the Oratory of Madonna del Rosario at Monte Mario to concentrate on composing, study, and prayer. By 1865 he had received minor orders, fulfilling his desire to offer a special ministry to his faith. Liszt wore the dress of an Abbé for the remainder of his life, outwardly demonstrating this deeper connection to the Church.

In 1869 the Grand Duke of Weimar encouraged Liszt to return to the city. Liszt had residency at the Hofgärtnerei, where he gave lessons and masterclasses until his death. This situation began what Liszt would call vie trifurquée, or “threefold life.” During this period, his time was divided among visits to Weimar for teaching; residing in Rome where he could devote time to his religious study and his relationship with Carolyne; and his appearances in Hungary, aiding the new Pest Academy of Music and becoming its official president in 1875. Such a grueling travel schedule, year after year, would be difficult for any individual, let alone a septuagenarian.

Liszt and his students, Liszt in the upper window

Photograph by Louis Held, Weimar 1883.

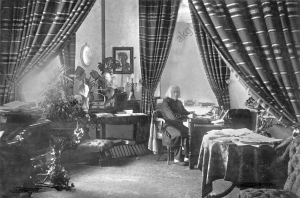

Liszt at his desk in the music room and study of the “Hofgärtnerei” in Weimar. 1885

His late music reflects the feelings of depression and sadness he was experiencing in this final decade. Many compositions can be seen as autobiographical – musical representations of his failing physical condition, the traumatic personal losses he endured, and his overall, unceasing preoccupation with death.

By his final year, Liszt’s health was quickly deteriorating – he had chronic heart problems, he was partially blind, and he was fully bloated with dropsy. In July of 1886, Liszt traveled to Bayreuth to support Cosima during the Wagner Festival. During the train ride, he contracted pneumonia; while in Bayreuth, fever wracked his body and he was consumed by an agonizing cough. On July 31 he entered a coma, from which he never awoke, and died later that evening. On August 3, 1886 the incomparable Franz Liszt was buried.

Portrait Of Franz Liszt, 1886

Mihaly Munkacsy

[1] “Yes, ‘Jesus Christ on the Cross’, a yearning longing after the Cross and the raising of the Cross – this was ever my true inner calling; I have felt it in my innermost heart ever since my seventeenth year, in which I implored with humility and tears that I might be permitted to enter the Paris Seminary.” Will of Franz Liszt written Sept. 14 1860. Merrick, p. 61.

[2] Walker, Vol. I, p. 144.

[3] Walker, Vol. II, p. 557.

[4] The entanglements concerning this annulment are far too many to go into detail for this particular document. Great insight can be provided by Liszt, Carolyne, and the Vatican: The Story of a Thwarted Marriage As It Emerges from the Original Church Documents (Franz Liszt Studies Series).